Grand Unified Theory

| Beyond the Standard Model | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Standard Model

|

||||||||||

The term Grand Unified Theory or GUT, refers to any of several similar models in particle physics in which at high energy scales, the three gauge interactions of the Standard Model which define the electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions, are merged into one single interaction characterized by a larger gauge symmetry and one unified coupling constant rather than three independent ones. The physics of most models of grand unification cannot be discovered directly at particle colliders because the new particles they predict have masses close to the Planck scale. Instead, information about grand unification might be obtained through indirect observations such as proton decay or the properties of neutrinos. [1] Some grand unified theories predict the existence of magnetic monopoles.

Unifying gravity with the other three interactions would form a theory of everything (TOE), rather than a GUT. Likewise, models which do not unify all interactions using one simple Lie group as the gauge symmetry, but constitute variations of the idea, for example using semisimple groups, can exhibit similar properties and are sometimes referred to as Grand Unified Theories as well.

| Are the three forces of the Standard Model unified at high energies? By which symmetry is this unification governed? Can Grand Unification explain the number of Fermion generations and their masses? |

Contents |

History

Historically, the first true GUT which was based on the simple Lie group SU(5), was proposed by Howard Georgi and Sheldon Glashow in 1974.[2] The Georgi–Glashow model was preceded by the Semisimple Lie algebra Pati–Salam model by Abdus Salam and Jogesh Pati,[3], who pioneered the idea to unify gauge interactions.

Motivation

The fact that the electric charges of electrons and protons seem to cancel each other exactly to extreme precision is essential for the existence of the macroscopic world as we know it, but this important property of elementary particles is not explained in the Standard Model of particle physics. While the description of strong and weak interactions within the Standard Model is based on so-called gauge symmetries governed by the simple symmetry groups SU(3) and SU(2) which allow only discrete charges, the remaining component, the so-called weak hypercharge interaction is described by an abelian symmetry U(1) which in principle allows for arbitrary charge assignments.[note 1] The observed charge quantization, namely the fact that all known elementary particles carry electric charges which appear to be exact multiples of 1⁄3 of the "elementary" charge, has led to the idea that hypercharge interactions and possibly the strong and weak interactions might be embedded in one Grand Unified interaction described by a single, larger simple symmetry group containing the Standard Model. This would automatically predict the quantized nature and values of all elementary particle charges. Since this also results in a prediction for the relative strengths of the fundamental interactions which we observe, in particular the weak mixing angle, Grand Unification ideally reduces the number of independent input parameters, but is also constrained by observations.

Grand Unification is reminiscent of the unification of electric and magnetic forces by Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism in the 19th century, but its physical implications and mathematical structure are qualitatively different.

Unification of matter particles

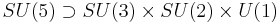

SU(5)

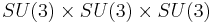

SU(5) is the simplest GUT. The smallest simple Lie group which contains the standard model, and upon which the first Grand Unified Theory was based, is

.

.

Such group symmetries allow the reinterpretation of several known particles as different states of a single particle field. However, it is not obvious that the simplest possible choices for the extended "Grand Unified" symmetry should yield the correct inventory of elementary particles. The fact that all currently known (2009) matter particles fit nicely into three copies of the smallest group representations of  and immediately carry the correct observed charges, is one of the first and most important reasons why people believe that a Grand Unified Theory might actually be realized in nature.

and immediately carry the correct observed charges, is one of the first and most important reasons why people believe that a Grand Unified Theory might actually be realized in nature.

The two smallest irreducible representations of  are

are  and

and  . In the standard assignment, the

. In the standard assignment, the  contains the charge conjugates of the righthanded down-type quark color triplet and a lefthanded lepton isospin doublet, while the

contains the charge conjugates of the righthanded down-type quark color triplet and a lefthanded lepton isospin doublet, while the  contains the six up-type quark components, the lefthanded down-type quark color triplet, and the righthanded electron. This scheme has to be replicated for each of the three known generations of matter. It is notable that the theory is anomaly free with this matter content.

contains the six up-type quark components, the lefthanded down-type quark color triplet, and the righthanded electron. This scheme has to be replicated for each of the three known generations of matter. It is notable that the theory is anomaly free with this matter content.

The hypothetical righthanded neutrinos are not contained in any of these representations, which can explain their relative heaviness (see Seesaw mechanism).

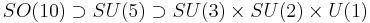

SO(10)

The next simple Lie group which contains the standard model is

.

.

Here, the unification of matter is even more complete, since the irreducible spinor representation  contains both the

contains both the  and

and  of

of  and a righthanded neutrino, and thus the complete particle content of one generation of the extended standard model with neutrino masses. This is already the largest simple group which achieves the unification of matter in a scheme involving only the already known matter particles (apart from the Higgs sector).

and a righthanded neutrino, and thus the complete particle content of one generation of the extended standard model with neutrino masses. This is already the largest simple group which achieves the unification of matter in a scheme involving only the already known matter particles (apart from the Higgs sector).

Since different standard model fermions are grouped together in larger representations, GUTs specifically predict relations among the fermion masses, such as between the electron and the down quark, the muon and the strange quark, and the tau lepton and the bottom quark for SU(5) and SO(10). Some of these mass relations hold approximately, but most don't (see Georgi-Jarlskog mass relation).

Unification of forces and the role of supersymmetry

The unification of forces is possible due to the energy scale dependence of parameters in quantum field theory called renormalization group running, which allows parameters with vastly different values at collider energies to converge at much higher energy scales. [4]

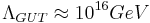

The renormalization group running of the three gauge couplings has been found to nearly, but not quite, meet at the same point if the hypercharge is normalized so that it is consistent with SU(5) or SO(10) GUTs, which are precisely the GUT groups which lead to a simple fermion unification. This is a significant result, as other Lie groups lead to different normalizations. However, if the supersymmetric extension MSSM is used instead of the Standard Model, the match becomes much more accurate. In this case, the coupling constants of the strong and electroweak interactions meet at the so-called GUT-Scale

.

.

It is commonly believed that this matching is unlikely to be a coincidence. Also, most model builders simply assume supersymmetry (SUSY) because it solves the hierarchy problem—i.e., it stabilizes the electroweak Higgs mass against radiative corrections.

(For a more elementary introduction to how Lie algebras are related to particle physics, see the article Particle physics and representation theory.)

Neutrino Masses

Since Majorana masses of the right-handed neutrino are forbidden by SO(10) symmetry, SO(10) GUTs predict the Majorana masses of right-handed neutrinos to be close to the GUT symmetry breaking scale. In supersymmetric GUTs, this scale tends to be larger than would be desirable to obtain realistic masses of the light, mostly left-handed neutrinos (see neutrino oscillation) via the seesaw mechanism.

Proposed theories

Several such theories have been proposed, but none is currently universally accepted. An even more ambitious theory that includes all fundamental forces, including gravitation, is termed a theory of everything. Some common mainstream GUT models are:

|

|

Not quite GUTs:

|

|

Note: These models refer to Lie algebras not to Lie groups. The Lie group could be [SU(4)×SU(2)×SU(2)]/Z2, just to take a random example.

The most promising candidate is SO(10). (Minimal) SO(10) does not contain any exotic fermions (i.e. additional fermions besides the Standard Model fermions and the right-handed neutrino), and it unifies each generation into a single irreducible representation. A number of other GUT models are based upon subgroups of SO(10). They are the minimal left-right model, SU(5), flipped SU(5) and the Pati-Salam model. The GUT group E6 contains SO(10), but models based upon it are significantly more complicated. The primary reason for studying E6 models comes from E8 × E8 heterotic string theory.

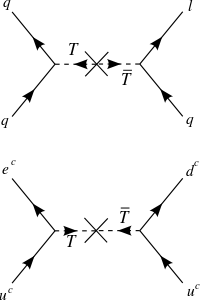

GUT models generically predict the existence of topological defects such as monopoles, cosmic strings, domain walls, and others. But none have been observed. Their absence is known as the monopole problem in cosmology. Most GUT models also predict proton decay, although not the Pati-Salam model; current experiments still haven't detected proton decay. This experimental limit on the proton's lifetime pretty much rules out minimal SU(5).

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the |

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the |

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the triplet Higgs |

Some GUT theories like SU(5) and SO(10) suffer from what is called the doublet-triplet problem. These theories predict that for each electroweak Higgs doublet, there is a corresponding colored Higgs triplet field with a very small mass (many orders of magnitude smaller than the GUT scale here). In theory, unifying quarks with leptons, the Higgs doublet would also be unified with a Higgs triplet. Such triplets have not been observed. They would also cause extremely rapid proton decay (far below current experimental limits) and prevent the gauge coupling strengths from running together in the renormalization group.

Most GUT models require a threefold replication of the matter fields. As such, they do not explain why there are three generations of fermions. Most GUT models also fail to explain the little hierarchy between the fermion masses for different generations.

Ingredients

A GUT model basically consists of a gauge group which is a compact Lie group, a connection form for that Lie group, a Yang-Mills action for that connection given by an invariant symmetric bilinear form over its Lie algebra (which is specified by a coupling constant for each factor), a Higgs sector consisting of a number of scalar fields taking on values within real/complex representations of the Lie group and chiral Weyl fermions taking on values within a complex rep of the Lie group. The Lie group contains the Standard Model group and the Higgs fields acquire VEVs leading to a spontaneous symmetry breaking to the Standard Model. The Weyl fermions represent matter.

Current status

As of 2009[update], there is still no hard evidence that nature is described by a Grand Unified Theory. Moreover, since the Higgs particle has not yet been observed, the smaller electroweak unification is still pending.[5] The discovery of neutrino oscillations indicates that the Standard Model is incomplete and has led to renewed interest toward certain GUT such as  . One of the few possible experimental tests of certain GUT is proton decay and also fermion masses. There are a few more special tests for supersymmetric GUT.

. One of the few possible experimental tests of certain GUT is proton decay and also fermion masses. There are a few more special tests for supersymmetric GUT.

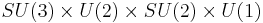

The gauge coupling strengths of QCD, the weak interaction and hypercharge seem to meet at a common length scale called the GUT scale and equal approximately to  GeV, which is slightly suggestive. This interesting numerical observation is called the gauge coupling unification, and it works particularly well if one assumes the existence of superpartners of the Standard Model particles. Still it is possible to achieve the same by postulating, for instance, that ordinary (non supersymmetric)

GeV, which is slightly suggestive. This interesting numerical observation is called the gauge coupling unification, and it works particularly well if one assumes the existence of superpartners of the Standard Model particles. Still it is possible to achieve the same by postulating, for instance, that ordinary (non supersymmetric)  models break with an intermediate gauge scale, such as the one of Pati-Salam group.

models break with an intermediate gauge scale, such as the one of Pati-Salam group.

See also

- Grand unification energy

- Fundamental interaction

- Particle physics and representation theory

- Classical unified field theories

- X and Y bosons

- B-L quantum number

Notes

- ↑ There are however certain constraints on the choice of particle charges from theoretical consistency, in particular anomaly cancellation.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Ross, G. (1984). Grand Unified Theories. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-805-36968-7.

- ↑ Georgi, H.; Glashow, S.L. (1974). "Unity of All Elementary Particle Forces". Physical Review Letters 32: pp. 438–441. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.32.438.

- ↑ Pati, J.; Salam, A. (1974). "Lepton Number as the Fourth Color". Physical Review D 10: pp. 275–289. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.275.

- ↑ Ross, G. (1984). Grand Unified Theories. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-805-36968-7.

- ↑ Hawking, S.W. (1996). A Brief History of Time: The Updated and Expanded Edition. (2nd ed.). Bantam Books. p. XXX. ISBN 0553380168.

Notations

- An account of the origin of the term GUT

- Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time, includes a brief popular overview.

boson

boson  in

in  in flipped

in flipped  and the anti-triplet Higgs

and the anti-triplet Higgs  in

in